Introduction

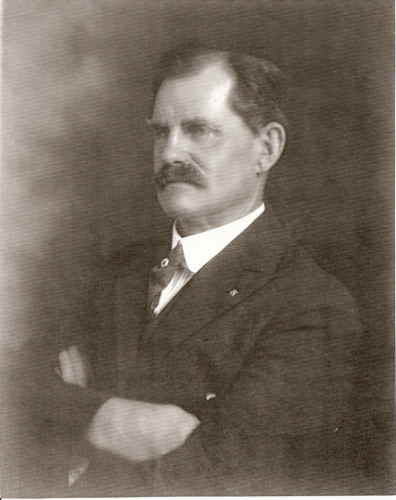

Richard Brackenbury features in our Pioneers Chart for two simple reasons:

- He was a genuine pioneer in humanity and business through his settlement in the USA via the ‘Medicine Bow Valley Pioneers’

- His actions and moral compass throughout his business dealings and in the twilight of his business work, have proven to be the benchmark/yardstick in that rarest of commercial interests, compassion for the less privileged; in the cut and thrust world of ‘opening up the Union’, Brackenbury emerged as a veritable ‘saint’, dispelling the notion that it does not matter who or what you damage in your quest to ‘get to the top’ - this is essentially why hardly anyone has ever heard of him.

His life and work

Brackenbury was born in Woolwich, England on the 3rd June 1864 to Charles Booth Brackenbury and Hilda Eliza Brackenbury (née Campbell) - he married Katharine Gibbs at Waltham Abbey on the 22nd March 1893 - together they raised six sons in the United States; Lionel Beaumont, Richard Athelstan, Charles Maurice, William Launcelot, Gabriel Keith and John Geoffrey Morland.

Rising to the rank of Vice President at the Carbon Bank, Brackenbury became known as ‘The Philosopher Poet’ in addition to his ‘rancher’ tag - young Brackenbury had first arrived in the United States at the age of sixteen in 1880 to work as an interpreter for an Italian colony that dissolved shortly after his arrival - his ties with England were firm and frequent when he stayed ‘in touch’ with relatives and friends.

Brackenbury had travelled extensively with his father, who was a Colonel Commander of an important British fortress - whilst in South Africa Richard had become familiar with the trading of wool and this was to become a cornerstone of knowledge in his future development.

Unlike most boys that came from well-ordered aristocratic English homes, Richard baulked at the idea of joining the militia or the army - instead he simply went along with everything that such an upbringing yielded including a private education, whilst harbouring the intent of ‘becoming his own man’.

After three years schooling at Sandhurst, Kansas, Brackenbury dropped out of education and together with a close friend, who heralded from Wiltshire, built a covered wagon, stocked it with bedrolls, pots and pans and headed for Wyoming, arriving there in 1884 at the age of twenty.

He landed a job supplying hay to stage stations north of Fort Fetterman; he spent the winter hunting and trapping with his partner until they reached the banks of the Medicine Bow Valley River - fastidiously saving his money from England he homesteaded in the middle of the prairie not far from Carbon, he purchased a local ranch. Over time he acquired a six mile stretch of the Medicine Bow Valley, where he raised broodmares and traded cattle and sheep on his, by now named, ‘Anchor Ranch’, named after the anchor which was his brand.

His friend from Wiltshire had no money of his own and earned his keep by doing the kitchen and mechanical work; shortly after the pair had settled in they were joined by another schoolmate, in his mid-twenties, from England who had a substantial allowance and wanted to settle also in the ‘wild west’. The new addition to the fold had one side of his face and nose seriously disfigured by Lupus such that he kept the condition covered by a black scarf - despite having a wonderful English home he felt he was a considerable embarrassment to his parents and all who set eyes on him - the wild west offered him freedom to do as he wished and he spent time chopping wood, riding and doing other chores - visitors to the ranch delighted at his wavy brown hair, sparkling brown eyes, musical laugh and banjo playing.

Brackenbury soon reasoned that ticks and scabs took an immense toll on sheep in this country and he set about tearing down the old loafing sheds he found, concluding that bunches of sheep corralled into a small place was a breeding ground for disease. His sheep soon became accustomed to the harsh winters and his herders sought shelter from the same in the draws and washes and in the willows along the waterways.

He also learned that good coalminers did not necessarily make good ranchers or cowboys; for that matter neither did young aristocratic Englishmen who attended the finest schools, but lacked basic living skills - he set up an apprentice school where for $500 young English boys learned to become competent all round ranch hands; a schooling that also enabled them to qualify in the business of ranching. A handful of the graduates were the young chaps he brought with him from England ... Thornhill, Hebeler, Fred Fee and Murray (who later became ranchers on Rock and Dutton Creek), the Horne Brothers (ranchers on the Medicine Bow) and Ben Schoonjans of the Elk Mountain area.

NB: It was not easy to establish and maintain a frontier community. Aside from the harassment from the Native Americans, there were the usual petty jealousies and worse, a total lack of law enforcement. Fortunately there were individuals whose leadership would overcome the desire for personal gain and supplant the community effort. These were people who wanted something more and sacrificed to make it happen - Richard Brackenbury was one of these people - he showed true dedication, he demonstrated a process that includes men and women who wanted to be a part of something greater than them; this is a process that is pretty uncommon today, but was common in frontier Wyoming.

In 1893 Brackenbury built the main house, a long low structure on the homestead, he also refurbished a house on the adjoining ranch and he was now ready to travel back to England to bring back his ‘bride to be’, together with a business partner and several young English boys, who he intended to turn into ranch hands; the spring of 1893 saw Brackenbury, his wife Katharine and her servant girl Lizzie, his first real business partner Dick Bowles and his wife Mae, and six young men arrive at Ellis Island. After the vast amount of luggage and freight were loaded on the westbound train, Dick Bowles and his wife and the young men boarded and set off for Anchor Ranch; Brackenbury, with Lizzie in tow, took his wife on a ‘honeymoon visit’ to Niagara Falls.

Brackenbury’s new wife, a refined, educated young woman from one of the notable socialite English families, wrote copious letters to friends and family; in particular no less than eight letters to her mother gave great insight to the term ‘city girl meets the wild West’.

After swinging and swaying across the United States, stopping off in Chicago to see the World Fair, their train finally arrived in Laramie, Wyoming; while the Brackenbury’s conducted business in Laramie, Lizzie went on to the town of Carbon with the luggage - Carbon, Wyoming, was one of the Medicine Bow Valley’s ghost towns, where the first coal mine was opened by the Union Pacific Railroad.

On resuming their journey, the two engines, pulling the long train carrying Brackenbury and his bride, struggled in the dark against hurricane force winds that drove thick snow into blinding white-outs before the engineer’s window; they arrived five hours late in Carbon where old friend William Evans had waited to greet them. Evans had become alarmed at seeing the engines struggling against a steep gradient and such forceful winds that he witnessed a coach being tossed aside the railroad causing the passengers and luggage to be thrown into the inky blackness and deep snow beside the tracks.

Finally, the Brackenbury’s and Evans climbed into the wagon headed, so they all thought, for a nice warm bed; the team drawing the wagon, however, was encountering deep snow and the journey proved a tricky navigation. Against Brackenbury’s wishes, Evans whipped the team up causing the horses to lunge and effect the most hair-raising, breath-taking introduction to the Wyoming frontier.

The young Mrs B, keeping a notable stiff British ‘upper lip’, wrote of her night’s stay in the Evans’ family home:

Arrived at the Evans’ home, we soon tumbled into bed with the usual lack of bolsters, blankets and baths - but they were very kind. Mr Evans is a shopkeeper in Carbon; it feels so strange staying with people like that. They are always so hospitable; no false shame of their poor little home prevents their asking you, puts many of our English people to shame. They had a sweet little baby who cried all night and a sweet mouse, which likewise squeaked and a sweet cat that walked in at the window to catch the mouse and a sweet parrot that aroused us early by cries of ‘Papa, Come here’ - it was rather nice when morning came.

Katharine Brackenbury found her new surroundings to be an absolute dream and she commenced to setting up routines and task schedules for all in her ‘chain of command’; a good example of this was the classically established Sunday routine for all - Breakfast at 7.30 am, after lunch a stroll about the property, followed by an afternoon of hymn singing with Katharine reading form the Bible - this proved to be the foundation of ‘homesteading life’.

Between her numerous household duties, including, washing clothes, ironing, baking, cooking, cleaning, mending and preparing grocery lists and planning meals Katharine dealt with her fair share of outside chores like tending the chickens and other farm animals - clearly her drive coupled with her caring nature endeared her to all who encountered her. She took ‘ambulance lessons’ and as a result of this was able to tend to the broken collar bone of one of the aides - henceforth there commenced an impressive nursing and doctoring career for the young bride, so far away from home and her brand of civilisation - mostly what captures the imagination about Katharine Brackenbury was the oft-spoken phrase ‘behind every great man lies a great woman’ - in the case of Richard and Katharine Brackenbury this is undoubtedly the case.

Although the Brackenbury’s had set up home in a notionally idyllic setting, when it came to ‘going to town’ Katharine was not enamoured with Carbon at all - she writes at the time:

Carbon is really too horrid; it is just like a great rubbish heap with wooden shanties pitched on the top here and there and everywhere - they say nearly all the children die and no wonder with such arrangements. We put up the horses and had dinner (lunch) at the Hotel and afterwards wandered around shopping for three hours. Everything we wanted was so expensive it was aggravating - the drive home was the coldest I have ever experienced

Shortly after their arrival, the Brackenbury’s soon found themselves experiencing ‘Western Style Hospitality’; ranchers would drop by unannounced for lunch and it was not long before the Brackenbury’s were discussing just how much food and drink a hungry Ranch hand could devour at each meal.

One of the perils of early summer was susceptibility to ‘mountain fever’, usually caused by the cold winds sweeping down from the high ground in early May - no-one appeared to be immune from the condition and Richard in particular suffered very badly, so much so that arthritis soon set in even though he was a relatively young man - the Wyoming weather left him stiff, sore and fatigued at a time when the general medical care for the complaint was bed rest and tonics.

The general concern from Katharine during all this was that the dirt just seemed to get everywhere - even a gentle sweep through the house caused considerable disturbance to dust; in order to record such issues Katharine sent for a camera and started taking pictures of the locals upon whom she commented - ‘they do wear such funny garments’ .

Soon more of their goods and chattels arrived from England including fine tea sets, glasses and real silverware; gone were the mugs without handles, iron ‘silverware’ and three pronged forks. Katharine had brought the English aristocracy to the West.

In mid-May Richard and Katharine would pack a picnic buggy and set out for the sheep range where the annual sheep count took place. Parking his wife upwind of some 2,880 odorous critters, Richard started assisting the Ranch hands in counting the sheep and starting them on the 10 mile trip to the shearing pens at Medicine Bow. By mid-morning the day was turning out to be a scorcher and Richard, together with Katharine went on ahead to Medicine Bow to arrange shearing; Katharine observed Medicine Bow to be ‘a funny little place’.

MEDICINE BOW, WYOMING - ELEVATION 6605 feet Latitude 41.90 - Longitude 106.20

Population 279 (2013) - home of Owen Wister's 'Virginian'.

Historians say over 20,000 people a year crossed the Medicine Bow Valley on the

Overland Trail.

In addition to her organisational duties, Katharine set about recording daily events on her camera - as Richard expanded his stock and business she would observe the hard work that all were undertaking as stock was brought into the corrals.

Richard would, from time to time, need to leave his wife at the Ranch and set off for Medicine Bow or Carbon to conduct business there. Oft-times sandstorms would blow up and set daytime temperatures to freezing despite being in the high 80’s just an hour or two before; Katharine has noted in her diaries that on one occasion the meat ration became low and she ordered the killing of a pig to resume stock levels; unaccustomed to Wyoming’s spring weather with no refrigeration and the fluctuations in climate, no-one considered what the week ahead might hold in meteorological terms; after a week of soaring temperatures and the consumption of a lot of fresh pork, most of the help spent days in their bunks recuperating.

Once sheep shearing had been completed, usually towards the end of May, Richard and his hands would need to drive the flock back to the Anchor Ranch; even in May heavy snow and bitter winds could fight them all the way and it was quite normal for a tired and sick Richard to go on ahead with one of the hands to seek the comfort of a warm bed. On one occasion, late in the day, Richard came across a hired hand who had lost the sheep he was herding homeward - leaving the hired hand to take the wagon home Richard untied his horse from the unit and set off in search of the lost sheep. Late that night with the sheep safely corralled in a neighbouring ranch, the rancher revived Brackenbury with fresh warm clothes and some stiff drinks. On returning home stiff, sore and very cold, Richard was treated to a warm fire, a hot bath and warm towels topped off with a recuperating massage from his wife.

Having secured the flock on the Ranch for the summer, the Brackenbury’s would take time out to visit Salt Lake by stagecoach - the friendliness of the occupants on the coach and the pleasant demeanour of the driver caused Katharine to remark upon same - the Brackenbury’s would avail themselves of the hot salt springs and return to the Anchor Ranch, via the freight train to Ogden and the passenger train with sleeping quarters, fully refreshed for the later stages of summer.

Cutting the hay in late July tended to end the ‘mosquito season’, which the Brackenbury’s could avoid by tripping to Salt Lake; anyone who has lived through the mosquito season in Medicine Bow would fully appreciate Katharine Brackenbury’s loathing of that time of year - she notes ‘the nasty horrible biting insects swarm so thick, it is impossible to beat them off’.

Katharine would drape her dress in a mosquito net, wearing leather gloves and thick rubber boots, which still enabled her to walk around the ranch premises. Wild pink rose bushes in full bloom grew in mass profusion across the landscape hiding the annoying gopher holes that lay beneath them; she dared not run to catch the butterflies’ skitting from rose to rose for fear of injuring herself via a gopher ‘den’. A bluebird’s nest with little blue eggs, the snow-cap on Elk Mountain, the sweet smell of the mountain air mixed with the perfume of a million summer flowers in full bloom, were enough to erase the misery of the hard times she was becoming accustomed to.

Despite any mosquito ‘plague’, Richard would oft-times take the crew to a July 4th celebration picnic; Katharine, accompanied by Lizzie in the buggy, would transport iced drinks and the food for the occasion. Richard would use such events to ‘break’ broncos from the Ranch and would often become painfully unseated in the process whilst trying to demonstrate the art of his prowess - such bucking, heaving and snorting from the broncos often unsettled the docile buggy team.

Once the show was over, the group headed out over the irrigation ditches and fallen trees to the Medicine Bow River swollen substantially by melting snows, ensuring a hair-raising journey back to the Anchor Ranch.

Elk Mountain, Wyoming: home of the renowned GARDEN SPOT PAVILION with the famous

"swing and sway" dance floor. "If you can't dance, hop on and ride!"

Dancers from everywhere danced to the music of Harry James, Lawrence Welk, Tommy

Dorsey, T.Texas Tyler and many more famous bands.

Katharine Brackenbury’s letters, the source of much of the material in this piece, ceased on July 16th 1893; this text contains a great deal of anxiety about the horse breakers and their treatment of the broncos, since it was not uncommon for a horse to perish in this process - she remained disenchanted also with the gophers as they appeared to be ‘taking over the place’.

In a sense the Brackenbury’s had brought a style of feudal humanitarianism to the wild west, combining the landowning aristocracy from whence they came with an intuitive sense of ‘benefactorism’ towards their ‘charges’ - Richard Brackenbury built a significant property portfolio but nowhere is there any evidence of malpractice to be found; indeed quite the opposite as the Brackenbury’s made friends and influenced for the good far and wide of their locale in Carbon - Richard’s rise to the Vice Presidency of the Carbon Bank is testament to this legacy that he left.

Five sons were born to the Brackenbury’s when they lived at the Anchor Ranch and a further son was born once they sold up and moved to Denver in 1905 (some say 1897, but there is little or no evidence for this) - the sale of the ranch was made to Christian Cronberg, a distant relative of Marvin Cronberg, the author of the book ‘Good Medicine for the Bow’ from which a good deal of this piece is sourced.

Richard Brackenbury went on to build an extensive sheep market by starting a very successful sheep commission business, handling sheep for practically all firms operating on the Denver Market; in the late 1890’s he had property in Grand Island, Lincoln and various other Nebraskan locations directly connected to the trail movements and sheep feeding - this was a visionary regime where he rounded up a few Wyoming and English investors and bought the shares that a few Denver Bankers owned in five hundred square miles of well-watered rangeland on the Mesa Mayo Range near Trinidad, Colorado; this meant that Brackenbury then owned the largest sheep ranch in Colorado State where he also ran two to three thousand head of cattle.

In the 1930s with the depression deepening, Richard and his partner (Dick Bowles) sold out. Paying off his investors and his partner; Brackenbury earned the respect of sheep men by financing them and discounting their notes at both western and eastern markets.

Often referred to as the ‘Philosopher Poet’, he retired to La Jolla, California where he kept up with old friends, his writing and poetry - he died there on the 18th June 1956.

Timeline:

- Birth 3 June 1864, Woolwich, Kent, England

- Arrival in US - 1879 - aged 15 years

- Return to US - 1885 - aged 21 years

- Return to US - 1886 - aged 22 years

- Marriage to Katharine Gibbs - 22 Mar 1893 - aged 28 years - Waltham Abbey, Essex, England

- Return to US via Queenstown, Ireland - 22 January 1897- aged 32 years

- Residence - Montclair, Arapahoe, Colorado - 1900 - aged 36 years

- Arrival Liverpool England - 10 July 1902 - aged 38 years

- Residence - Walnut, Phillips, Kansas 1910 - aged 46 years

- Residence - Denver Ward 14, Denver, Colorado 1910 - aged 46 years

- Residence - Denver 1914 - aged 50 years

- Residence - Phillips, Kansas 1917 - aged 53 years

- Residence - San Diego, California 1920 - aged 56 years

- Residence - San Diego 1930 - aged 66 years

- Residence -San Diego 1st April 1940 - aged 75 years

- Death - La Jolla, San Diego 18th June 1956 - aged 92 years

- Burial - San Diego Cemetery, California, USA

Close Family: Parents & Children

Father: Charles Booth Brackenbury: (1831 - 1890)

Mother: Hilda Eliza Campbell: (1832 - 1918)

Children:

- Lionel Beaumont Brackenbury: (1894-1950)

- Richard Athelstan Brackenbury: (1895-1962)

- Charles Maurice Brackenbury: (1897-1957)

- William Launcelot Brackenbury: (1898-1959)

- Gabriel Keith Brackenbury: (1902-1917)

- John Geoffrey Morland Brackenbury: (1906-1997)