Uncovering the hidden causes of massive losses

A wholesale mobile phones business had done well in the early days of high demand, growing both its customer base of retail outlets and levels of service to become a large and impressive business. But with the proliferation of customer types and enhanced levels of service there came another change. On a turnover of £250m it began to make £1.5m per month losses.

As sales volumes increased so profitability plummeted. Its share price followed. A tumble to 3% of its highest level. Shareholders became highly concerned.

Eliminating the root causes of the problem became the key to turning the business round.

The CEO set down three objectives:

- reduce the unit costs of all the processes

- reduce the capital tied up in stock

- eliminate any characteristics of doing business that made them a loss

Flaky processes

As the company experienced rapid growth it started to miss deadlines, suffer re-work, lose data, and fail on promises to customers. The lack of process robustness was at the root of a growing blame culture and the source of high process costs.

A core team of people drawn from each function set to work analysing each process to uncover the problems and gauge what could be done to fix them. By working with groups of people representing each process, rapid agreements to changes were brokered followed by an eager desire to get the improvements in place. But the process analysis pointed ominously to more serious issues.

Cost drivers

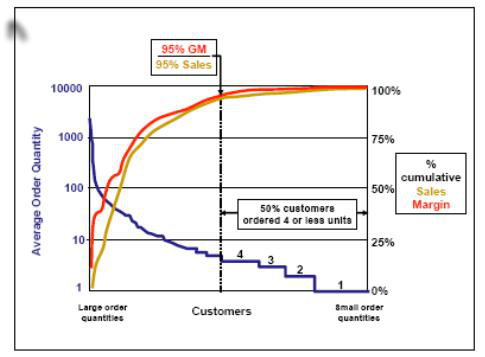

Suspicion fell on the order quantities that customers were placing. The figure below plots customers on the basis of reducing order quantity. The customer on the extreme left ordered the highest order quantities; around 2,000 products at a time. Customers on the right, about 20% of them, were only ordering one product at a time. Other variables plotted in the same sequence as the customers showed a startling result.

About 50% of the customers ordered 4 or less units per order. These orders only added the last 5% of sales value and gross margin. But will the last 5% of gross margin be sufficient to cover the cost of processing the orders?

The truth was that some types of orders created overheads far higher than the gross margin.

Inventory

With the growth in business volumes the company had acquired large warehousing facilities fuelled by a desire to improve service levels and an eye on opportunistic discount deals of large quantities of products from the manufacturers. But having lots of stock masked a number of underlying problems. Current popular products were often out of stock, products with predictable demand had unnecessary high stock cover, and there were mountains of stock of unpopular lines.

The analysis showed that the ability of stock to retain a positive gross margin fell away rapidly after two months. Customers didn’t want old models. With 40% of the stock in this category it changed from being an asset to a liability and a major source of value erosion. A lack of forecasting and a history of making poorly justified purchases were the root cause.

Customer profitability

The Activity Based Costing (ABC) analysis found that the overriding cost driver in the business was the number of orders. Almost irrespective of the size of the order, each order drove much the same set of activities such as ‘order entry’, then ‘credit check’, then ‘pick & pack’, then ‘despatch, then ‘invoicing’. So for any orders where the gross margin was less than the order processing costs, those orders made a loss.

Suddenly the key issue dawned on everyone - far from believing that a positive gross margin was always good because it was making a contribution to overheads, if the real net profit was negative then more volume meant ever-increasing losses!

Attention now turned to resolving two questions:

- Were there particular customers who were placing orders which just lost them money every time?

- Why when volumes were increasing did growth seem to lead to declining overall profitability?>

The analysis looked at the characteristics of various customer segments. One particular segment, small High Street Dealers, mostly ordered small quantities of phones with an average order gross margin of only £15.

For the company as a whole the analysis had shown that the average cost to process an order was around £50 which meant that for the High Street Dealer segment, on average each order lost the company £35. This segment placed 87% of the orders accounting for over 50% of sales value!

Taken together with other analyses, these customers were the source of the falling profitability of the business as overall volumes and number of customers increased. The company’s apparent successful growth had really been in ever increasing unprofitable business.

By setting the minimum order value such that the gross margin was always greater than £50 ensured no unprofitable orders were taken. Most customers complied with the new minimum order values. Those that threatened to take their business to competitors were encouraged to do so. The competitors would welcome the business but unwittingly would be taking on a significant loss.

It was now very apparent that the policy of paying the sales force a bonus based on gross margin led to the sales force driving the business into the ground. Sales people didn’t realise that their decisions filled the warehouse with unnecessary stock or that selling costs for low volume business were high, or that the majority of the orders were for very small amounts.

If the net profit was negative but the gross margin positive, they still got their bonus.

Benefits demonstrated by this project

The key lesson for this company was the ease by which they were blinded by apparent success. The founder and CEO of the business realised that the money he had raised by going plc had mostly gone into growing the physical size of the company to service unprofitable business.

Initially the City had measured success in sales volume terms. Also share prices in the sector had rocketed for everyone so a true measure of performance was obscured for a considerable time. The salesforce were generating positive gross margins and collecting bonuses, so they weren’t complaining. No signals came from the Sales Director of the impending problems.

The standard financial reports didn’t report on net profit at the product or customer level or on the relationship between costs and cost drivers, so even the finance function were blind to the underlying drift to disaster.

Tracking the changes to net profit is not ordinarily shown in the management reports. It takes time and effort to unearth the real relationships between costs and the drivers of costs, and to understand how the relationships to certain customer segments sow the seeds of disaster as volumes increase.

At the 11th hour the change in selling policy to a minimum order quantity that ensured that the gross margin always covered the costs of processing the order meant that profit wasn’t haemorrhaging from the business. However, the change back to profitability came with a large reduction in total volume sales as customers who wanted to remain in an unprofitable relationship were simply turned away.

Profitability came at the price of reduced volumes of orders to process which meant fewer people were needed, housed in less space and without the need for the huge warehouse.

When companies are growing it should be a business imperative to have the tools and techniques of analysis to determine the real net margins of products and customers.

This will ensure they avoid the pitfalls that can so easily turn the trend of apparent roaring success into a spiral of decline that is hard to slow down.